|

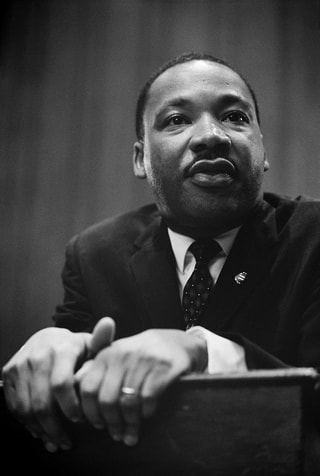

“I remember a lot about that day,” she said, answering the interviewer. Personally, I felt out of place. I was standing on the outskirts of a small but crowded room, watching intently as reporters quizzed Ruby Bridges, the now 65-year-old who was the first African-American child to be integrated into William Frantz, an all-white elementary school in Louisiana. “I believe that I was protected, and a lot of what protected me was my innocence. I actually thought it was Mardi Gras,” said the Louisiana native. Bridges learned within minutes that the large and angry crowd screaming outside of her new school wasn’t celebrating, but were protesting her, a then six-year-old girl with a vivid imagination and innocence.. After her interview with the press during the speaking event, which was held at Methodist University where I work in the marketing and university relations department, Bridges was filed into the auditorium. Myself and my coworkers made our way to the front row, eagerly waiting to hear her speak again. After a formal introduction, Bridges stood behind the pulpit, preaching a familiar story, but with far more detail than I could have imagined. RUBY BRIDGES’ BRAVE JOURNEY

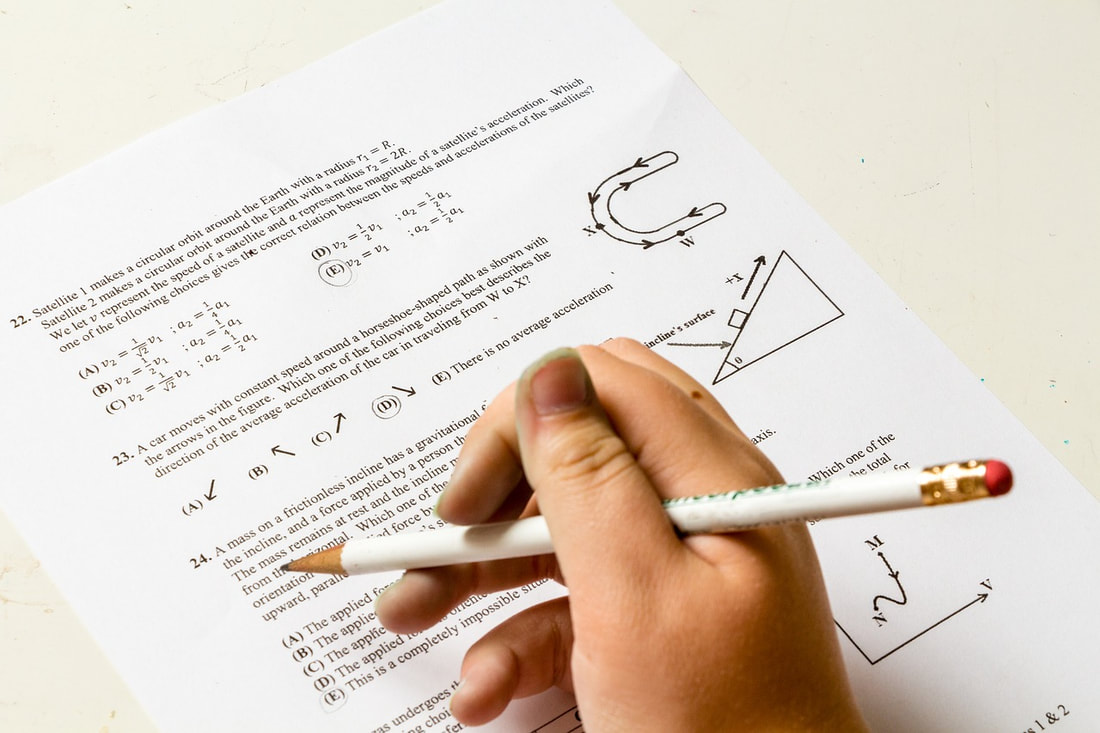

Although her father fought side by side with white men during the war, often sharing foxholes and the possibility of being killed during combat, he was still made to go to separate bunks and eat in separate mess halls. He was pretty against her attending an all-white school at first, but he gave in and allowed her to take a special test that would decide which African-American students were “worthy” of attending school with white children. The test was hard. It was made that way purposefully to try and guarantee that no African-American child could make it to the classroom. However, six students passed the rigged test. “I take pleasure in saying all six were girls,” Bridges jested. Bridges was set to be one of three of the girls integrated into William Frantz Elementary School, while the other three were set to integrate into another all-white school in the area. However, Bridges’ parents were faced with a difficult decision when the two children who were to attend the school with Bridges decided to drop out of the integration program. Even though Ruby wasn't able to go to school with other African-American children, she recalled that she was surrounded by men and women from her neighborhood who wanted to see her off to school. “I remember all of my mother’s friends coming over saying ‘we are going to help her get dressed this morning,’” she recalled.

When they arrived to the school, scores of people were there, holding picket signs, throwing things, and shouting racial slurs. One woman even had a small African-American doll resting in a baby casket. But with clear instructions from her escorts, Ruby marched into school and into the principal's office, where she sat all day waiting to be put into a classroom. But no teacher would take her. When Barbara Henry decided to add Ruby to her classroom roster, parents pulled their white children from school. For a full year, Ruby sat in a classroom with her teacher, learning and growing every day. WHAT BRIDGES TAUGHT ME

She didn’t care what the person who stayed with her son until she could get there looked like. All that mattered was that she got to spend some time with him before he passed.

“Racism is just one tool that is used to divide us,” she said. “We need to take back this nation, but it’s evil we need to take it back from.” As one-half of an interracial couple, and someone who met their other half in college, I was happy and humbled to learn the true bravery of not only Ruby, but also her mother and father and those other girls who integrated into a separate all-white school. When watching clips from movies that retell Ruby's story, I find myself overwhelmed in trying to put myself in their shoes. Without the strides made in the civil rights movement by African-Americans and others who supported change, I wouldn't have met my husband. I wouldn't be married to the love of my life. He might not even exist, because he is a product of an interracial marriage. I am eternally grateful to no longer live in a world where we are separate, but I'm blessed and honored to live in a world where we can be joined together as one in marriage. But one thing is clear: we are still yet to be fully integrated. There are still many all-white schools, and there are many schools that are majority African-American. We should work to make sure that every child knows that they are equal to the next. They should all get equal access to education and should never, regardless of income, race, or the neighborhood they live in, be excluded from a school. By integrating our schools more thoroughly, we are forging a bright future that is culturally and historically aware of the social issues facing minorities in the United States. This is the best way to ensure that the cruel and ugly past doesn't continue to repeat itself.

4 Comments

|

Details

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed